June 10, 2025 Story by: Publisher

Alabama has started appealing the lengthy redistricting fight, aiming to bring the racial discrimination case back to the U.S. Supreme Court.

An appeal was filed June 6 by Secretary of State Wes Allen, state Sen. Steve Livingston, R-Scottsboro, and Rep. Chris Pringle, R-Mobile.

The filing asks the Supreme Court to consider a May federal court ruling on Allen v. Milligan, in which judges found the Alabama Legislature to have intentionally discriminated against Black voters and violated the Voting Rights Act and the 14thAmendment through a 2023 congressional district map drafted by the state’s Legislature.

The three-judge panel that heard the case ruled the 2023 map may not be used in future elections.

Under Alabama’s existing 2021 redistricting plan—approved by the GOP‑controlled state Legislature—the state maintained one black‑majority district (District 7). Civil rights advocates challenged the map, arguing that it diluted Black voting strength in violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA) and the 14th Amendment.

In June 2023, the Supreme Court, in Allen v. Milligan (599 U.S. 1), ruled 5–4 that Alabama must create two black‑majority congressional districts. The Court held that the 2021 map likely violated the VRA and reaffirmed the lower court’s injunction requiring a second majority‑Black district.

May 2025 Ruling and Political Implications

In a May decision, the three-judge panel—two judges appointed by President Trump—issued a rare rebuke of legislative maneuvering:

“Try as we might, we cannot understand the 2023 Plan as anything other than an intentional effort to dilute Black Alabamians’ voting strength and evade the unambiguous requirements of court orders standing in the way,” the judges wrote in last month’s ruling.

The panel ruled the map was impermissible for future elections and invited plaintiffs to seek restoring pre‑clearance under the VRA, potentially placing Alabama once again under federal oversight for election law changes. The court set a June 9 deadline for parties to clarify which district map would govern until 2030, and whether pre‑clearance should be imposed.

State’s Strategy: Appeal and Tactics

Responding swiftly, Secretary Allen, Livingston, and Pringle announced in their appeal that Alabama would halt any further congressional map revisions until 2030. Their stated goal is to counter any VRA pre‑clearance requirements and avoid legislative re‑map obligations.

By petitioning the Supreme Court to hear the case again, Alabama’s leadership contends that the lower courts misapplied Allen v. Milligan and that the judges exceeded their authority by disenfranchising the Legislature’s map‑drawing process.

Following the federal court’s redistricting, Alabama’s District 2 elected Rep. Shomari Figures, D-Alabama, marking the first Black Alabamian to be elected to Congress outside of District 7 since Reconstruction.

Background

Alabama has had at least one majority-Black U.S. House district – the 7th – since 1992, but plaintiffs argued that it failed to give proper representation to Black Alabamians, who make up about 27% of the state’s population but, with a single majority-Black district, only made up 14% of Alabama’s U.S. House delegation. The three-judge panel struck down the 2021 map in 2022, ruling that racially polarized voting in Alabama meant that Black Alabamians could not select their preferred leaders.

Alabama was one of several states covered by Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

From its enactment until 2013, any changes to Alabama’s voting laws – including redistricting plans – required federal approval, either by the U.S. Justice Department or a D.C. federal court, before taking effect.

In Shelby County v. Holder (2013), however, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the coverage formula that triggered Section 5 for Alabama and other jurisdictions.

The Court left Section 5 in place but effectively rendered it unenforceable absent a new formula. As the Justice Department explains, after Shelby “jurisdictions identified by the coverage formula in Section 4(b) no longer need to seek preclearance… unless they are covered by a separate court order entered under Section 3(c) of the Voting Rights Act”.

Section 3(c) of the VRA – allows a court to impose preclearance on a jurisdiction if it finds intentional discrimination in violation of the Fourteenth or Fifteenth Amendments. In that event, the court can require the jurisdiction to “submit for preapproval any voting qualification or prerequisite to voting or standard, practice, or procedure with respect to voting” for a time the court deems appropriate. Unlike the now-defunct Section 4 coverage formula, Section 3(c) has no expiration date.

Thus, plaintiffs in the Alabama case have asked the court to invoke Section 3(c) and force the state to get federal approval before making any new redistricting changes.

Recent Court Rulings and Allen v. Milligan

These federal issues arose from a lengthy legal challenge to Alabama’s congressional maps. In 2022, a three-judge federal court struck down Alabama’s 2021 map, ruling that it violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act by diluting Black voting power.

The court noted that Black Alabamians make up about 27% of the state’s population but under the old plan held only one of seven U.S. House seats (roughly 14% of representation). With voting patterns sharply polarized by race in Alabama, the court concluded that Black voters could not elect their preferred candidates in a second district under the 2021 plan.

The court ordered the state to draw a map with two districts in which Black voters would have a realistic opportunity to elect their chosen candidates.

The U.S. Supreme Court upheld that ruling.

In Allen v. Milligan, 599 U.S., the Court agreed that plaintiffs were likely to prevail on their Section 2 claim against Alabama’s 2021 map. The Court’s 5-4 decision effectively mandated creation of a second majority-Black district.

In response, the Alabama legislature approved a new map in 2023 with one majority-Black district and a second district that was roughly 40% Black. The federal panel, however, still found that map intentionally discriminated against Black voters for failing to produce two Black-opportunity districts as required by law.

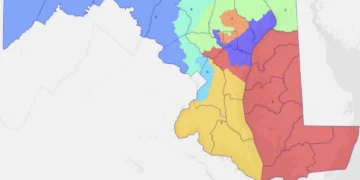

After trial, the three-judge court appointed a special master who drew a remedial map. That map shifted boundaries so that Alabama’s 2nd and 7th congressional districts are majority-Black or nearly so.

It was used in the 2024 elections, and the result was historic: for the first time, Alabama elected two Black members to the U.S. House simultaneously. Republicans won five other seats, as in prior years.

In its 2025 opinion, the panel explicitly found the 2023 legislative map was the product of racial intent, saying the Legislature had “purposefully refused” to comply with prior court orders.

Source: Alabama Political Reporter / Shelby County v. Holder, 570 U.S. 529 / Allen v. Milligan, 599 U.S.