Jay Cossey participates in a bingo game with fellow residents during activity time at The Retreat at Kenwood assisted living facility in Texarkana, Texas, on Friday, May 17, 2024. After suffering multiple strokes over seven years ago, which resulted in significant short-term memory loss, the former lawyer moved into this facility. He is one of the few Black residents, living just blocks away from his previous apartment. Credit: AP Photo/Mallory Wyatt.

May 28, 2024 Story by: Editor

Norma Upshaw, 82, residing alone south of Nashville, was advised by her doctor to start in-home dialysis.

Her nearest family lived 40 miles away and had already scrambled once when her previous independent senior living facility, predominantly serving Black residents, closed with just 30 days’ notice. They were now searching again for an assisted living facility or an affordable apartment closer to home.

Unable to find suitable options, Upshaw’s daughter added a small apartment to her home.

“Most of her doctors, her church, everything was within Nashville,” said Danielle Cotton, Upshaw’s granddaughter. “… this was the best option for us.”

Nearly half of Americans over 65 will eventually require some form of long-term health care. This sector is rapidly shifting from nursing homes to community living situations.

An analysis by CNHI News and The Associated Press revealed that Black Americans are less likely to use residential care communities, such as assisted-living facilities, and more likely to reside in nursing homes. In contrast, white Americans are more prevalent in residential care communities.

Experts and those in the assisted-living industry are aware of this disparity, attributing it to various factors, including personal and cultural preferences, insurance coverage, and the geographic location of residential care communities. These factors differ by state and family.

Consequently, older Black Americans may miss out on living arrangements that foster community, prevent isolation, and assist with daily tasks while maintaining some independence.

“The bottom line is white, richer people have a solution now — which is these incredible assisted-living communities — and minorities and low-income people don’t,” said Jonathan Gruber, an economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “That is the fundamental challenge facing our country as our demographics are shifting.”

Complex Causes

The AP and CNHI News analysis of the National Post-acute and Long-term Care Study, published in 2020, found that Black individuals are underrepresented in residential care communities by nearly 50%.

Black Americans constitute about 9% of people over 65 in the U.S. However, they only make up 4.9% of those in residential care communities, while they represent about 16% of nursing home residents.

In contrast, white Americans, who account for 75% of the over-65 population, are 88% of those in residential care communities. Other ethnic and racial groups are also underrepresented in assisted living facilities, but only Black Americans are overrepresented in nursing homes.

| Source: National Center for Health Statistics, U.S. Census Bureau. Table source: apnews.com |

The lack of a universal definition for assisted living led the federal study to create the “residential community care” category, encompassing settings that support people who cannot live independently but do not require the comprehensive care provided by nursing homes.

These communities offer help with daily activities like bathing, dressing, and managing medications without providing round-the-clock nursing care.

Financial barriers significantly impact low-income people of all races, but they are more pronounced for older Black Americans. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Black workers earn $878 weekly compared to $1,085 earned by white workers, a gap that has persisted for decades.

This wage disparity affects both the ability to pay for long-term care and homeownership rates. Many residents fund senior care by selling their homes, yet more than 7 in 10 homeowners in the U.S. are white, according to 2020 U.S. Census Bureau data.

Assisted living facilities cost an average of $4,500 per month or $54,000 per year, according to the National Center for Assisted Living. Most people pay privately through personal funds or long-term care insurance; nursing homes can be covered by Medicaid. This financial structure places assisted living out of reach for many Black Americans, explained Cotton, who also runs a Nashville nonprofit helping financially strapped seniors find housing.

She noted that many seniors struggle to afford even government-subsidized housing, let alone expensive living communities: “It leaves them in a gap. Those are the seniors that are really not even considered or thought about.”

In Palo Alto, California, the nonprofit Lytton Gardens uses funding from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development to subsidize housing costs for low-income assisted living residents. However, the cost of care — scheduled meals, help with bathing, and taking medications — remains the individual’s responsibility.

Efforts to reach Black and Hispanic seniors through social workers, libraries, and senior centers have not significantly diversified the resident population, which remains predominantly white and Asian.

“Most of the time, I’m begging somebody to move in,” said Donna Quick, housing administrator for Lytton Gardens. “But it’s just a matter of finding somebody who has the funds for this assisted living program.”

The process of paying for long-term care is “as opaque as it can be,” said Linda Couch, senior vice president of policy and advocacy at LeadingAge, a nonprofit representing long-term care providers and researchers. “Because we don’t have a comprehensive and cohesive long-term care financing system in this country, we are left with this patchwork,” Couch explained.

Researchers also question whether the increasing number of assisted living facilities is located near Black communities, but answering this is challenging.

“The federal government doesn’t even have a list of assisted living (facilities),” said Lindsey Smith, a researcher in health systems management and policy at Oregon Health and Science University-Portland State University School of Public Health. “There is not, like, a registration. When COVID hit, they did not have a list.”

Desire to Stay Home

LaShuan Bethea, executive director of the National Center for Assisted Living, emphasized the need for more research to determine if fewer Black people in assisted living means they are missing out on necessary care or if they are finding support in other ways.

“It’s really important to do the work … trying to understand: What does this mean when Black and brown people can’t access assisted living, knowing what it brings in terms of quality and outcomes?” Bethea said.

While affordability is a key factor, it does not entirely explain the lower numbers of Black people in assisted living.

“There’s also the expectation of wanting to keep people home as long as possible,” said Candace Kemp of Georgia State University’s Gerontology Institute. “And within families of color, African American communities in particular, there’s this desire to take care of family members.”

Steven Nash’s father could afford the most expensive assisted living facilities but preferred to stay home. Nash, who ran one of the last remaining Black-owned nursing homes in the Washington, D.C., area, helped care for his father until he passed away at 87.

“Even though it was very difficult for the family, we still kept that promise,” Nash said. “We try as hard as we can to honor the wishes of our elders.”

As smaller nursing homes and facilities catering to Black residents close, a cultural competency gap emerges. Nash noted that cultural food options are often replaced with generic menu items.

“People want to live out their life the way they’ve lived,” he said.

Indiana state Sen. Gregory Porter’s 95-year-old mother still lives in her home of six decades, cared for by Porter, other family members, and in-home health professionals. Porter’s daughter has promised to care for him similarly as he ages, providing him “a level of comfort.”

“It means a lot,” Porter said. “It gives you the will to live.”

However, assisted living can offer independence for those whose daily needs are increasing.

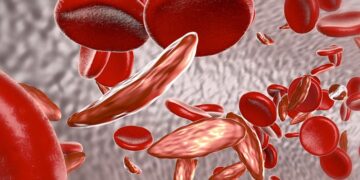

Older Black Americans are twice as likely to have Alzheimer’s or other dementias compared to older white people, according to the Alzheimer’s Association. Nash observed a growing interest in assisted living for dementia care among Black Americans; he plans to open a specialized facility soon.

In Texarkana, Texas, former lawyer Jay Cossey moved into an assisted living facility after multiple strokes over seven years ago left him with significant short-term memory loss. He is one of a few Black residents in a facility near his old apartment.

His church community encouraged the 70-year-old to move in, despite his family in Alabama wanting him to live with them.

“My brother came and said he wanted to take me home,” Cossey recalled. “I told him I am home. I’m home because I feel good here.”

Gerber reported from Kokomo, Indiana; Shastri reported from Milwaukee; and Forster reported from New York.