May 12, 2025 Story by: Publisher

A federal appellate court is set to hear a case Tuesday centered on a five-year debate over whether the national right-leaning group ‘True the Vote’ used mass voter challenges to intimidate minority voters.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit will hear arguments in a case in which plaintiffs, including a voting rights group founded by Stacey Abrams, contend that the case has national implications. Attorneys from both sides will have 15 minutes to present their cases during Tuesday’s hearing.

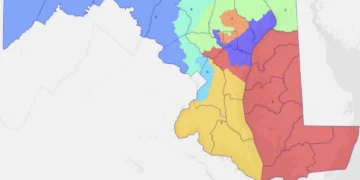

The decades-long battle over Georgia’s political maps drawn after the 2020 Census has reignited after the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals agreed to hear arguments on whether to impose revised district lines.

At issue is whether maps approved by the Republican-controlled legislature unlawfully dilute the voting power of Black Georgians, in violation of the Voting Rights Act.

Background of the Legal Challenge

Shortly after Republican lawmakers in Atlanta approved new districts in late 2021, civil-rights groups filed multiple suits—including Common Cause v. Raffensperger, Pendergrass v. Raffensperger, Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. v. Raffensperger, and Grant v. Raffensperger—arguing that the maps violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act by packing and cracking Black voters into fewer winnable districts.

In October 2023, U.S. District Judge Steve C. Jones struck down Georgia’s original congressional map and two state legislative maps, finding that they “likely dilute the voting strength” of Black Georgians, and ordered the General Assembly into a special session to redraw them. The Legislature’s subsequent revisions, however, created only one additional opportunity district—falling short of the plaintiffs’ demand for two majority-Black or coalition minority districts.

Key Contested Districts

A flashpoint remains Georgia’s 7th Congressional District, which had been a coalition-majority district—27% Black, 21% Hispanic, and 15% Asian—before it was reconfigured in 2021 to favor a Republican candidate.

That redrawing led Democratic incumbent Lucy McBath to shift her campaign to the 6th District in 2022, opening the 7th for Republican Rich McCormick

Marina Jenkins, executive director of the National Democratic Redistricting Committee, denounced the legislature’s approach as a “robbing Peter to pay Paul” tactic that zeroes out statewide Black voting strength.

Similarly, challengers fault the state’s legislative map for eliminating or weakening Black-opportunity districts in and around Macon-Bibb, Savannah, and Augusta, even as Georgia’s Black population grew by nearly half a million between 2010 and 2020.

Appeals Arguments

Plaintiffs argue that under the Supreme Court’s Inclusive Communities decision (2015), Section 2 protects minority voters from districting plans that “submerge” them into districts where they cannot elect their preferred candidates. They seek either restoration of the pre-2021 coalition districts or the creation of new majority-Black districts that reflect Georgia’s changing demographics.

State defenders maintain that the Voting Rights Act requires only that minority voters have the opportunity to elect their candidates in truly majority-Black districts—not coalition districts. In court filings, the state asserts that plaintiffs are seeking a “partisan gerrymander under the guise of civil-rights enforcement” and that the legislature’s maps comply with both federal law and Georgia’s constitutional requirements.

What Happens Next

Oral arguments before a three-judge 11th Circuit panel are scheduled for this week. If the appeals court upholds Judge Jones’s ruling, the special master–drawn maps used in the 2024 elections will remain in place through 2030. A reversal, however, could send the case back to the district court, force another round of map drawing, or prompt the state to seek Supreme Court review.

The state’s lawyers have defended the maps by arguing that the Voting Rights Act protects only districts where Black voters form an outright majority—not those where minority groups collectively constitute a majority. In court filings, they accused challengers of seeking partisan advantage under the guise of civil-rights enforcement, arguing: “The Voting Rights Act ‘is a balm for racial minorities, not political ones.’ It cannot be hijacked to settle partisan disputes.”).

As the appeals court prepares to hear oral arguments, both sides are watching closely. Plaintiffs seek to restore or create additional districts where Black voters have a fair chance to elect their candidates of choice; the state contends its revised maps meet federal standards and reflect legitimate legislative prerogatives.

That the case remains unresolved more than two years after the Census underscores the complex interplay between demographic change, partisan interests, and federal civil rights protections.

The 11th Circuit’s decision could set a critical precedent for how minority-driven population growth is translated into political representation—both in Georgia and nationwide.

Source: Georgia Recorder