Oct 11, 2024 Story by: Editor

Oct 11 (Reuters) – Recent research reveals that cancer patients with darker skin tones are more susceptible to severe cases of a painful side effect of radiotherapy, partially due to the limitations of the tool currently used to detect the condition, which is more effective in patients with lighter skin.

Each year, over four million U.S. patients undergo radiation therapy, and more than 90% of them experience radiation dermatitis, a form of skin burn. The main screening tool, approved by the National Cancer Institute to detect and assess the severity of this condition, relies on identifying skin reddening.

In this study, researchers monitored 60 racially diverse breast cancer patients for radiation dermatitis throughout a year of radiotherapy, using a spectrophotometer – a device typically used in industries like paint and cosmetics to analyze color.

The study found that while light-colored skin turns red during the development of radiation dermatitis, darker skin tends to darken instead.

Earlier research by the same team had already highlighted that, in patients with darker skin, doctors often do not diagnose radiation dermatitis until the skin starts to peel and scar. “That leaves patients treating their pain on their own, with over-the-counter creams and painkillers,” explained study leader Dr. Juhi Purswani of NYU Langone. She presented the findings at the American Society for Radiation Oncology meeting in Washington.

The researchers concluded that the current screening tool “likely under-captures radiation dermatitis in skin of color” and recommended that it be revised.

For Longer Life, Dieting ‘Success’ May Need a New Definition

Traditional markers of successful dieting, such as weight loss and metabolic improvements, may not be the key to extending lifespan, new laboratory experiments suggest.

In a study involving nearly 1,000 mice subjected to calorie restriction or intermittent fasting, those who lost the least weight actually lived longer than those who shed the most, researchers reported in Nature.

According to a commentary accompanying the report, which calls the study “one of the biggest studies of dietary restrictions ever conducted in laboratory animals,” the findings challenge conventional beliefs about how dietary restriction extends life, opens new tab.

Overall, the study showed that consuming fewer calories had a more significant positive effect on lifespan than intermittent fasting. However, animals that lost the most weight on these diets exhibited lower energy, compromised immune and reproductive systems, and had shorter lifespans.

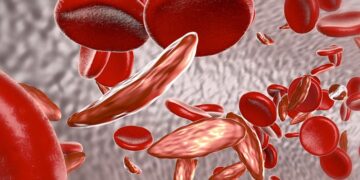

The researchers suggest that moderate calorie restriction might strike the best balance between long-term health and longevity. Factors most strongly linked to a longer lifespan included the ability to maintain body weight during periods of stress, strong immune cell function, red blood cell health, and higher body fat levels in later life.

Interestingly, metabolic responses commonly associated with dietary restriction, like lower fasting blood sugar levels, were not connected to longer life.

“The most robust animals keep their weight on even in the face of stress and caloric restriction, and they are the ones that live the longest,” said Gary Churchill, the study leader from The Jackson Laboratory in Bar Harbor, Maine, in a statement.

The findings also underscored that genetics play a more significant role in longevity than dietary restriction.

“If you want to live a long time, there are things you can control within your lifetime such as diet, but really what you want is a very old grandmother,” Churchill humorously remarked. Source: Reuters