Jan 15, 2025 Story by: Editor

Research from the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing reveals that hospitals serving a disproportionate number of Black patients often have higher patient-to-nurse ratios, potentially impacting patient outcomes.

Consider two patients in acute care: one in a unit where three nurses manage five patients and three manage six, and another in a unit where all six nurses handle six patients. Evidence consistently links higher nurse staffing levels to better outcomes, including reduced mortality and infection rates.

This scenario underscores findings from a recent study published in Nursing Research. Researchers discovered that nurse staffing rates are lower in hospitals with the highest percentage of Black patients—referred to as high-Black-serving hospitals (high BSHs).

“It’s particularly concerning because seven out of 10 Black patients are hospitalized in Black-serving hospitals, so there’s really a population implication for the Black patient population,” stated Eileen T. Lake, lead author and professor at Penn Nursing, who also serves as associate director of the Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research.

Key Findings

Adjusting for unit type, researchers found that nurses in high BSHs had 6% more patients per nurse compared to their counterparts in low BSHs. This adjustment was necessary as high BSHs had a higher percentage of survey respondents working in adult intensive care units, which typically have fewer patients per nurse. Further adjustments for factors such as hospital academic status and location revealed a 7% higher ratio.

The study’s authors propose two potential solutions: directing Black patients to hospitals with better staffing or improving staffing levels in high BSHs, with the latter deemed more practical.

Study Context and Implications

Data for the study was drawn from a 2015 survey of 179,336 registered nurses in 574 hospitals. Researchers suspect staffing disparities have persisted or worsened since, exacerbated by the pandemic’s disproportionate effects on marginalized populations and healthcare providers.

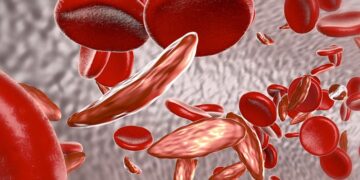

Previous studies found that care for Black patients is often concentrated in certain hospitals due to residential segregation. These facilities generally report higher mortality rates for both Black and white patients. Notably, earlier work by Penn Nursing professor J. Margo Brooks Carthon highlighted that Black patients are more affected by inadequate nurse staffing than white patients.

Addressing a perceived contradiction in past findings, the study authors wrote, “These seemingly contradictory findings may be interpreted as equity as a population level but inequity in localized areas for hospitalized older adults.”

Future Directions

Eileen T. Lake and her team continue to examine disparities in healthcare outcomes. Their research spans from neonatal care to older adults, with recent work highlighting higher levels of moral distress among nurses in high BSHs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ongoing investigations also suggest that adverse outcomes related to nursing care—such as bloodstream or urinary tract infections—are more prevalent in high BSHs. The team is exploring whether hospitals are “structurally competent” to address the needs of vulnerable groups.

“We’re trying to reveal a variety of core elements to how nursing might be a modifiable system feature that we could better deploy through better nurse staffing,” Lake explained. “Another construct we focus on a lot is nurses’ work environment.”

Study Contributors and Funding

The study’s co-authors include Hal Chen, Christin Iroegbu, Kimi Li, and Nehemiah Weldeab from Penn Nursing; Jessica G. Smith from the University of Texas at Arlington; Douglas O. Staiger from Dartmouth College; and Jeannette Rogowski from Penn State University.

The research was supported by the American Nurses Foundation and the National Institute of Nursing Research (T32NR007104). Source: Penn Today