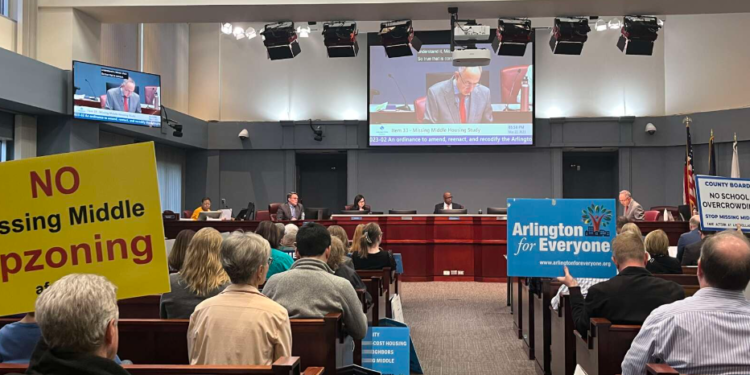

Attendees at the Arlington County Board meeting Wednesday, March 22 on Missing Middle Housing (staff photo)

July 9, 2024 Story by: Editor

As the highly anticipated Missing Middle trial commenced this week, the Arlington NAACP emphasized its significant implications for racial equity.

In a 55-page amicus brief submitted before Monday’s opening statements, the local NAACP chapter argued that single-family zoning has racist origins and that reversing Missing Middle would hinder racial progress.

“Plaintiffs claim that Arlington County’s decision to reform its exclusionary zoning scheme was arbitrary, capricious, and unreasonable,” the organization wrote. “In light of the history and harms of Arlington’s prior zoning policies, and the benefits of making them less restrictive and more inclusive, the County’s decision is reasonable beyond any fair debate.”

The group had supported Missing Middle’s passage on similar grounds, while noting that further efforts are necessary to fully integrate Arlington neighborhoods.

Opponents of Missing Middle contend that homes built under the county’s Expanded Housing Option permits will still be too expensive to significantly impact Arlington homeownership. While the new housing types were intended to be affordable for households earning between $108,000 and $118,000 per year, the median household income of Black Arlington residents is currently around $74,000.

Equity arguments

The NAACP’s filing states that restrictive zoning laws “were intended to act hand-in-glove with restrictive covenants” — Jim Crow-era agreements aimed at segregating neighborhoods by preventing people of color from purchasing homes.

Segregationist developers, planners, and policymakers promoted the introduction of single-family zoning in Arlington’s first zoning ordinance in 1930.

“The most desirable neighborhoods would consist exclusively of detached single-family houses,” the filing notes. “And the residents who lived in those new houses should be exclusively white and middle-class. The desire for racial uniformity in neighborhoods was widely held among white Americans.”

The zoning ordinance banned the construction of duplexes and semi-detached homes almost everywhere in the county, including on undeveloped land. As few Black residents could afford single-family homes, the filing argues that this and other policy decisions caused Arlington’s Black population to drop from 38% of the county in 1900 to just 5% in 1960.

“Arlington’s residents, and almost every Arlington neighborhood, had become overwhelmingly white by then,” the NAACP chapter wrote. “This was no accident. It was the deliberate result of policies adopted and enforced across all levels of government.”

The median household income of Arlington’s white residents remains more than double that of Black residents: $153,739 compared to $74,472, according to county data. Due to this, “the typical single-family detached home in Arlington is out-of-reach for a higher share of Black households than for white households,” the filing says.

The NAACP argued that all these factors highlight the importance of this week’s civil trial.

“Neighborhood segregation is still a policy choice,” the group said. “Our elected leaders have the power to choose differently. And they have. By legalizing some multifamily housing in Arlington’s residential neighborhoods, the County Board has chosen to remove legal barriers that stand in the way of every neighborhood becoming a mixed-income, racially integrated community.”

The trial

The Missing Middle trial is set to continue in Arlington Circuit Court until at least Thursday. Plaintiffs, citing procedural concerns, are arguing that the court should nullify the zoning changes.

On Monday, Judge David Schell allowed deposition testimony from the county’s retained expert on the Expanded Housing Option, Partners for Economic Solutions.

The Arlington County Board unanimously approved the zoning change last year, but its composition has changed somewhat since then. Board member Susan Cunningham was elected last year on a platform opposing Missing Middle, and another Board seat remains up for grabs in November.

The Democratic nominee for County Board, JD Spain Sr., supports Missing Middle.

A GoFundMe campaign set up to benefit the plaintiffs continues to attract donations and has raised over $92,000 as of Tuesday afternoon. Source: APL Now