Jan 30, 2025 Story by: Editor

Mississippi has a deeply rooted history of voter suppression, with a law from 1890 that permanently removes the voting rights of individuals convicted of certain crimes. This practice, known as felony disenfranchisement, continues to affect approximately 55,000 people in the state today. In 2024, Mississippi lawmakers briefly considered lifting the ban on voting for some nonviolent offenders, but the proposal was ultimately rejected in January 2025.

Upon Mississippi’s admission to the union in 1817, White men retained exclusive control over decision-making. Following the Civil War, they used violence, intimidation, and Jim Crow laws to maintain political power, denying the formerly enslaved Black population their rights, even though they outnumbered the White population. Here’s a brief overview of how voter intimidation and voting rights have evolved in the state over the past 150 years:

1865: The Civil War ended, and enslaved people in Mississippi were freed, marking the beginning of Reconstruction. In 1860, Black people made up 55% of the state’s population.

1866: A federal civil rights bill was passed, but Mississippi’s White-controlled government enacted “Black Codes,” criminalizing behaviors such as unemployment and requiring Black individuals to get special licenses for activities like preaching and gun ownership, and forcing Black children to work for former slave masters.

1867: Under federal control, over 79,000 Black men registered to vote, and 94 delegates, including 16 Black men, were elected to write a new state constitution. By 1868, nearly 97% of eligible Black men were registered to vote.

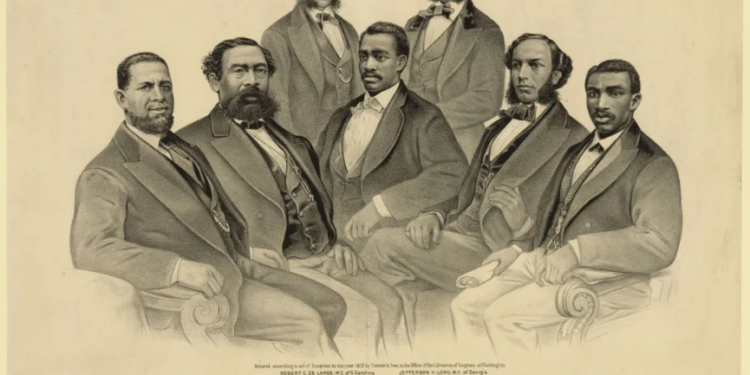

1869: Mississippi elected its first Black Secretary of State and Black legislators. By 1870, Black men made up 14% of the state Senate and 47% of the state House of Representatives. In the same year, Hiram Rhodes Revels became the first Black U.S. senator.

1870-1875: Black political representation flourished, including the election of a Black lieutenant governor in 1873 and another Black U.S. senator in 1874. By 1874, the state’s legislature had 69 Black members.

1875: White Democrats initiated the first “Mississippi Plan,” employing violence and intimidation to prevent Black people from voting. This led to several massacres, such as the Vicksburg Massacre in 1874, where as many as 300 Black people were killed, and the Clinton Massacre in 1875, where about 50 Black individuals died.

1877: Federal troops withdrew from Mississippi, marking the end of Reconstruction and the beginning of Jim Crow laws that legalized racial segregation.

1890: The state constitution was revised, adding felony disenfranchisement and implementing voter suppression tactics like literacy tests and poll taxes, part of a broader effort to invalidate the Black vote. By 1892, less than 6% of eligible Black men were registered to vote. Crimes such as bribery, theft, and arson were among those that led to the permanent loss of voting rights.

1910-1930: Many Black Mississippians left the state during the Great Migration, and by 1940, they no longer made up the majority of the population.

1950: The state removed burglary from the list of crimes that resulted in disenfranchisement.

1963: Mississippi’s racial violence and civil rights struggles became a national focus with the assassination of NAACP Field Secretary Medgar Evers. President John F. Kennedy subsequently called for a civil rights bill, but was assassinated later that year.

1964: President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the “Freedom Summer” efforts, led by civil rights groups, sought to register Black voters. Following the murders of activists James Chaney, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman by the Ku Klux Klan, Fannie Lou Hamer testified at the Democratic National Convention about the brutal treatment she faced when attempting to register.

1965: The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights held hearings on Mississippi’s discriminatory voting practices. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was passed, prohibiting racial discrimination in voting. A year later, Mississippi’s poll tax was ruled unconstitutional, and Black political participation began to increase once more, leading to the election of Robert G. Clark Jr., the state’s first Black representative since Reconstruction, in 1967.

1968: Murder and rape were added to the list of crimes that result in disenfranchisement.

1970s and beyond: Mass incarceration took root, both in Mississippi and nationwide. Since 1983, Mississippi’s prison population has increased by over 200%, according to the Vera Institute. While individuals not convicted of disenfranchising crimes can vote from prisons, many face obstacles accessing ballots.

1998: In Cotton v. Fordice, the U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the state’s felony disenfranchisement provision, removing the “discriminatory taint” despite previous changes to the state constitution.

2008: The Mississippi House of Representatives passed a bill to restore voting rights to those convicted of felonies, excluding murder and rape, but the bill was blocked in the state Senate.

2023: A three-judge U.S. 5th Circuit Court panel ruled that Mississippi’s lifetime voting ban violated the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on “cruel and unusual punishment.” However, the full appeals court agreed to reconsider the case, keeping the disenfranchisement laws intact.

March 2024: The Mississippi House of Representatives advanced legislation to restore voting rights to those convicted of some nonviolent crimes, but the bill died in the state Senate in April 2024.

July 2024: The full U.S. 5th Circuit Court voted to uphold Mississippi’s lifetime voting ban, overturning the earlier 2023 ruling.

January 2025: The U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear the case over Mississippi’s lifetime voting ban for the second time since 2023. Source: Mississippi Free Press