April 18, 2025 Story by: Publisher

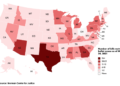

In the early 1980s, North Carolina’s legislative districting practices faced significant scrutiny for diluting the voting power of Black citizens. Luciel McNeel, a Black domestic worker in Mecklenburg County, highlighted the issue in 1984, noting that despite her consistent support for Black candidates since 1962, only two had been elected. The county’s multimember district system, dominated by a white voting majority, effectively marginalized Black voters’ influence.

This systemic issue led to the pivotal case of Thornburg v. Gingles, initially filed as Gingles v. Edmisten in 1981. Ralph Gingles and his colleagues challenged North Carolina’s redistricting plan, arguing it violated Section Two of the Voting Rights Act by producing racially discriminatory electoral outcomes. The case became the first to test the 1982 amendments to the Act, which shifted the focus from proving discriminatory intent to demonstrating discriminatory effects.

The 1982 amendment to Section Two of the Voting Rights Act was crucial in this case. It clarified that plaintiffs need only demonstrate that electoral processes have a discriminatory effect, rather than proving discriminatory intent. This change lowered the burden of proof for plaintiffs and was instrumental in the Gingles case, where the court found evidence of “legally significant racial bloc voting,” a key indicator of racial vote dilution.

In 1984, a special three-judge panel ruled in favor of Gingles, citing significant racial bloc voting that diluted Black electoral power. The decision mandated the creation of single-member districts to enhance minority representation. However, North Carolina and the Reagan administration appealed, arguing the ruling misinterpreted the Voting Rights Act. The Reagan administration’s Department of Justice, in its amicus brief, contended that the ruling could lead to courts striking down electoral schemes that did not guarantee proportional representation, a stance that was met with opposition from civil rights groups and some members of Congress.

The Supreme Court’s 1986 decision upheld the lower court’s ruling, affirming that North Carolina’s electoral process discriminated against Black voters. Justice William J. Brennan Jr. emphasized that multimember districting, which diluted minority votes, could not be justified by occasional benefits to minority voters. The Court’s decision validated the District Court’s findings that Black citizens were a distinct minority in each challenged district and faced systemic barriers to equal political participation.

Thornburg v. Gingles set a precedent for evaluating racial vote dilution, requiring courts to consider whether minority groups are sufficiently large, compact, and politically cohesive, and whether they face systemic barriers to electing their preferred candidates. This landmark case has been cited in approximately 700 subsequent cases, reinforcing the Voting Rights Act’s role in protecting minority electoral participation.

The decision marked a significant victory for civil rights, enabling greater political representation for minority communities. It underscored the transformative power of the Voting Rights Act, contributing to the election of over 10,000 Black officials nationwide, alongside many Latinx, Native American, and Asian American and Pacific Islander leaders. Thornburg v. Gingles remains a cornerstone in the ongoing fight for equitable voting rights, demonstrating the importance of addressing both the intent and effects of electoral practices.

Source: Legal Defense Fund