Dec 7, 2024 Story by: Editor

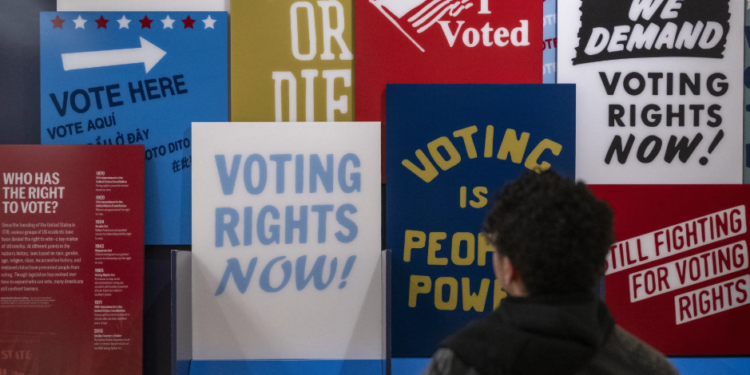

As Republicans prepare to take control of both Congress and the White House in the coming year, voting rights advocates are shifting their focus to state-level protections against racial discrimination in elections, bypassing reliance on federal measures.

In the past two decades, several states have enacted their own voting rights acts, with Michigan, a Democratic-led state, potentially joining the list soon. This week, a state House committee advanced Senate-approved bills to the House floor for consideration.

Supporters of such state-level laws view them as essential safeguards, especially as federal efforts to strengthen the Voting Rights Act remain stalled under a Republican-led government in Washington, D.C. The 1965 federal Voting Rights Act, a cornerstone of civil rights legislation, faces ongoing challenges, including a North Dakota lawsuit that could weaken its remaining provisions upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Adam Lioz, senior policy counsel for the Legal Defense Fund, emphasized the need for state-level action, saying, “We can expect attacks rather than progress at the federal level, and states must take up the mantle to protect their own voters.”

Currently, only eight predominantly blue states—California, Connecticut, Illinois, Minnesota, New York, Oregon, Virginia, and Washington—have enacted state-level voting rights acts. These laws provide stronger protections for racial minority groups than those available under federal legislation.

However, challenges to these laws persist. In New York, a state judge recently ruled that the state’s voting rights act violates the U.S. Constitution’s equal protection clause. The ruling arose from a case involving claims that the election system in Newburgh, New York, diluted the voting power of Black and Hispanic residents. Plaintiffs are appealing the decision, with oral arguments scheduled for December 18.

Despite legal hurdles, advocates like Lata Nott of the Campaign Legal Center argue that state-level protections empower voters to address discriminatory practices in local elections. “It allows voters to challenge laws that have a discriminatory impact. It gives voters the power to enforce their own right to equally participate in elections,” Nott said.

Efforts to enact such laws face significant challenges, even in blue states. In Maryland and New Jersey, legislation for state voting rights acts has stalled. Nuzhat Chowdhury of the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice expressed hope that the urgency of the 2024 elections would motivate lawmakers to act. “We hope and anticipate that the [2024 election] results really light a fire under them,” she said.

In Colorado, where similar legislation is being considered, funding remains a key concern. Aly Belknap, executive director of Common Cause Colorado, noted that the state’s budget constraints pose a challenge to implementing provisions like multilingual ballots and enforcement by the attorney general’s office.

Meanwhile, in Michigan, Lioz warned that Democrats’ narrow window to pass a state voting rights act is rapidly closing as Republicans are set to assume control of the state House next year. “If lawmakers don’t act soon, the chances go very substantially down,” he stated.

While state-level laws offer some protection, their limitations are clear. Over 50% of Black Americans reside in the South, where only Virginia has a Voting Rights Act. Spencer Overton of George Washington University’s Multiracial Democracy Project emphasized the importance of federal safeguards, saying, “If you are in a state without state voting protections, where you have incumbents who utilize discriminatory practices, you really do need federal protections.”

Advocates remain committed to pushing for state-level protections despite the political and legal challenges ahead. Source: WSHU