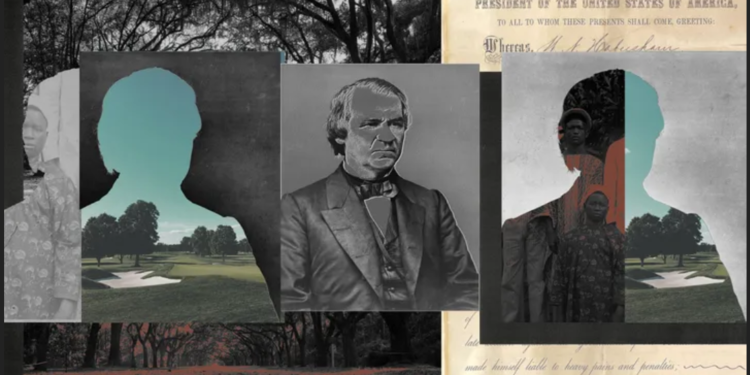

Credit: Illustration by Chris Burnett

June 26, 2024 Story by: Editor

40 Acres and a Lie unveils the history of a lesser-known government initiative that granted land titles to formerly enslaved individuals post-Civil War, only to reclaim nearly all of it within eighteen months. This in-depth exploration highlights the initial promise and subsequent betrayal, reflecting on its profound impact on Black Americans.

Pompey Jackson, born into slavery on Georgia’s Grove Hill estate, survived harsh conditions and smallpox. In 1864, as Union General Sherman marched through the South, thousands of enslaved individuals were freed. Sherman’s Special Field Orders, No. 15, issued in January 1865, promised land to the newly freed. This promise, often remembered as “40 Acres and a Mule,” was a significant, albeit short-lived, attempt at reparations.

Jackson was among the first in Georgia to receive a land title, granted 4 acres at Grove Hill in April 1865. Research by the Center for Public Integrity identified 1,250 formerly enslaved individuals, including Jackson, who received such titles in Georgia and South Carolina, based on records from the now-defunct US Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands.

The discovery of these records, many digitized in the last decade, revealed that land titles covered over 24,000 acres across 34 plantations. Despite initial success, by late 1865, under President Andrew Johnson, most of this land was returned to former Confederates, undermining the promise of Sherman’s orders.

The Freedmen’s Bureau records, digitized with help from the Mormon Church’s FamilySearch platform, provide crucial insights into Reconstruction. Historian Karen Cook Bell emphasizes the significance of these records in addressing reparations and understanding economic inequalities rooted in land access.

General Saxton, tasked with implementing Sherman’s orders, settled 40,000 freed people on designated lands. Among them were Eleaza Johnson and York Williams, who each received 40 acres on Skidaway Island. Freed people formed self-sufficient communities, electing representatives, forming militias, and working the land.

However, Johnson’s presidency marked a shift, as he pardoned ex-Confederates and reclaimed the land. Freedmen resisted, valuing their hard-earned land, but were ultimately overpowered by legal and military measures favoring former slaveholders.

Jackson’s 4-acre title became worthless by 1866, yet he remained in Georgia, working as a carpenter and raising a family. In 1894, he finally purchased land in East Savannah, contributing to a mutual aid society. Jackson’s descendants migrated north, pursuing better opportunities, and eventually acquiring property in Philadelphia.

Today, the land that was once Grove Hill is being developed into luxury estates, symbolizing the generational wealth denied to Jackson and his descendants. Historian William “Sandy” Darity Jr. notes the enduring impact of this broken promise on Black economic and political power.

Pompey Jackson’s story, spanning from Grove Hill’s rice fields to urban Philadelphia, underscores the resilience and determination of formerly enslaved families amidst systemic betrayal and ongoing struggles for equity and recognition. Source: Mother Jones