July 11, 2025 Story by: Publisher

A three-judge federal panel will hear arguments on July 29, 2025, to determine whether Alabama should be reinstituted under the Voting Rights Act’s preclearance requirement—a mechanism eliminated nationwide in 2013 but still invoked via the “bail-in” process for jurisdictions found to act with intentional discrimination.

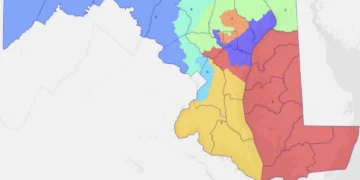

This hearing follows years of legal wrangling over Alabama’s congressional redistricting plans, which federal courts have repeatedly found to weaken Black political representation in violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

The panel—convening in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Alabama—will consider whether the state’s conduct warrants the imposition of Section 3(c) oversight. That provision allows courts to “bail in” a jurisdiction, requiring it to seek federal approval for any future changes to its voting laws or procedures for a defined period.

The plaintiffs in the case—Black voters and civil rights groups—argue that Alabama’s defiance of prior court orders and its repeated efforts to sidestep remedies that would ensure fair representation for Black residents amount to intentional and systemic racial discrimination. They assert that the state has engaged in what they call “strategic obstruction,” drawing comparisons to tactics used during the Jim Crow era to suppress minority voting power.

Central to their request is a demand that Alabama be placed under preclearance through at least the end of the decade. That would mean any new congressional map, including those that might arise following the 2030 Census, would require advance federal approval—either from the U.S. Department of Justice or the D.C. District Court—before taking effect.

The case stems from a 2023 decision in which the same three-judge panel ruled that Alabama’s post-2020 Census redistricting map violated the VRA by packing Black voters into one district and minimizing their influence elsewhere, despite the fact that Black residents make up more than a quarter of the state’s population. The court ordered Alabama to redraw the map to include two districts in which Black voters had a fair opportunity to elect candidates of their choice.

Federal judge response

In a May decision, the three-judge panel—two judges appointed by President Trump—issued a rare rebuke of legislative maneuvering:

“It would be remarkable — indeed, unprecedented — for us to hold that a state legislature that purposefully ignored a federal court order acted in good faith. It would be shocking for us to hold that a state legislature that intentionally ignored a federal court order for the purpose of (again) diluting minority votes acted in good faith. And it would be unthinkable for us to hold that a state legislature that purposefully took calculated steps to make a court-required remedy impossible to provide, for the purpose of entrenching minority vote dilution, acted in good faith,” the panel said.

The panel — comprised of U.S. Circuit Judge Stanley Marcus, a Bill Clinton appointee originally elevated to the federal bench by Ronald Reagan, U.S. District Judges Anna Manasco and Terry Moorer, both Donald Trump appointees — cited legislative actions, public statements, and procedural irregularities.

The panel heard arguments in the case during an 11-day trial featuring 23 witnesses and more than 2,600 pages of evidence. It rejected claims from members of the Legislature that they were acting in good faith.

“We are troubled by the state’s view that even if we enter judgment for the plaintiffs after a full trial, the state remains free to make the same checkmate move yet again — and again, and again, and again,” the panel wrote. “On the rare occasion that federal law directs federal courts to intrude in a process ordinarily reserved for state politics, there is nothing customary or appropriate about a state legislature’s deliberate decision to ignore, evade, and strategically frustrate requirements spelled out in a court order.”

The same three-judge panel in May permanently blocked Alabama from using the state-drawn map that they said flouted their directive to draw a plan that was fair to Black voters. The state is appealing that decision to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Alabama state officials told a federal court panel May that the state may delay drawing any new congressional district maps until 2030 in order to avert returning to federal oversight of its redistricting.

The Attorney General’s Office announced at a status hearing that legislative leaders would “voluntarily forgo any right to draw an additional congressional district map” as part of the remedial process. That move would effectively leave in place the court-ordered map with two districts that give Black voters a decisive say for the rest of the decade.

“We have been talking to the state about the possibility of perhaps resolving some or all of the remedial issues in this case, and that we would like the court to give us an opportunity to continue to have those discussions if they prove fruitful,” said Deuel Ross, an attorney with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund representing the plaintiffs, during the status conference.

Less than two hours before Wednesday’s hearing, attorneys for the state filed a court document stating that while they “maintain their arguments about the necessity and constitutionality of any remedial plan,” legislative leaders “will voluntarily forgo any rights that they may have to attempt to draw an additional congressional district map as part of remedial proceedings in this case.”

Instead, state lawmakers submitted a revised map that continued to feature only one majority-Black district. The panel rejected it, and a court-appointed special master was ultimately tasked with drawing a compliant map, which was used in the 2024 election cycle.

Now, plaintiffs argue that Alabama’s repeated defiance of federal rulings and its unwillingness to comply in good faith demonstrate a pattern of intentional discrimination that justifies extraordinary federal oversight. They cite not only the recent redistricting episode but also Alabama’s long history of suppressing Black voting rights through literacy tests, poll taxes, at-large elections, and other discriminatory mechanisms prior to the passage of the original Voting Rights Act in 1965.

Department of Justice response

The U.S. Department of Justice lodged a statement of interest in late June on the ongoing Alabama redistricting lawsuit—Allen v. Milligan (599 U.S. 1)—in the Northern District of Alabama, urging the court to reject plaintiffs’ request that Alabama be required to preclear all future congressional redistricting plans under Section 3(c) of the Voting Rights Act.

Three sets of plaintiffs filed lawsuits arguing that two congressional districts in Alabama should be majority Black. The Court found that Alabama’s attempt to create a second majority-Black district was insufficient.

Alabama agreed to use the Special Master’s Remedial Map going forward and has explained to the Court that it will not seek to redistrict again until after the 2030 Census. One plaintiff argues that it is insufficient and seeks Section 3(c) relief.

“The issues raised by the plaintiffs in this case have been remedied by the State of Alabama’s agreement to use the Remedial Map and pledge to not seek to redistrict again until after the next Census—over five years from now,” United States Attorney Prim Escalona for the Northern District of Alabama said. “The plaintiffs’ request to impose preclearance would unnecessarily tax principles of equal sovereignty that afford Alabama the Constitutional right to manage its own elections.”

An appeal was filed June 6 by Secretary of State Wes Allen, state Sen. Steve Livingston, R-Scottsboro, and Rep.Chris Pringle, R-Mobile.

“Preclearance flips the burden on the State to prove its innocence. That power is extraordinary,” Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall’s office wrote in a court filing opposing the request.

The Justice Department is backing Alabama in asking the judges to reject the request.

“Preclearance is permissible only when jurisdictions have engaged in pervasive, flagrant, widespread, and rampant discrimination,” Justice Department lawyers wrote in the filing signed by the acting chief of the voting section. Alabama’s actions did not rise to that level, they argued.

The Bail-In vs. Preclearance Mechanism

- Preclearance: Under Section 5 (declared inoperable since Shelby County v. Holder in 2013), certain jurisdictions had to seek federal approval before implementing voting changes.

- Bail-In Provision: Under Section 3(c), courts can impose case-by-case preclearance on states “bail(ed) in” for purposeful discrimination.

- Plaintiffs’ Request: Black voters and civil-rights groups now ask the court to impose bail-in, mandating federal review of any congressional map changes through 2030.

Recent Court Rulings and Allen v. Milligan

These federal issues arose from a lengthy legal challenge to Alabama’s congressional maps. In 2022, a three-judge federal court struck down Alabama’s 2021 map, ruling that it violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act by diluting Black voting power.

The court noted that Black Alabamians make up about 27% of the state’s population but under the old plan held only one of seven U.S. House seats (roughly 14% of representation). With voting patterns sharply polarized by race in Alabama, the court concluded that Black voters could not elect their preferred candidates in a second district under the 2021 plan.

The court ordered the state to draw a map with two districts in which Black voters would have a realistic opportunity to elect their chosen candidates.

The U.S. Supreme Court upheld that ruling.

In Allen v. Milligan, 599 U.S. U.S. ____ (2023), the Court agreed that plaintiffs were likely to prevail on their Section 2 claim against Alabama’s 2021 map. The Court’s 5-4 decision effectively mandated creation of a second majority-Black district.

In response, the Alabama legislature approved a new map in 2023 with one majority-Black district and a second district that was roughly 40% Black. The federal panel, however, still found that map intentionally discriminated against Black voters for failing to produce two Black-opportunity districts as required by law.

Source: Alabama Public Radio / AP News