Feb 24, 2025 Story by: Editor

A Guide to Safe Travel

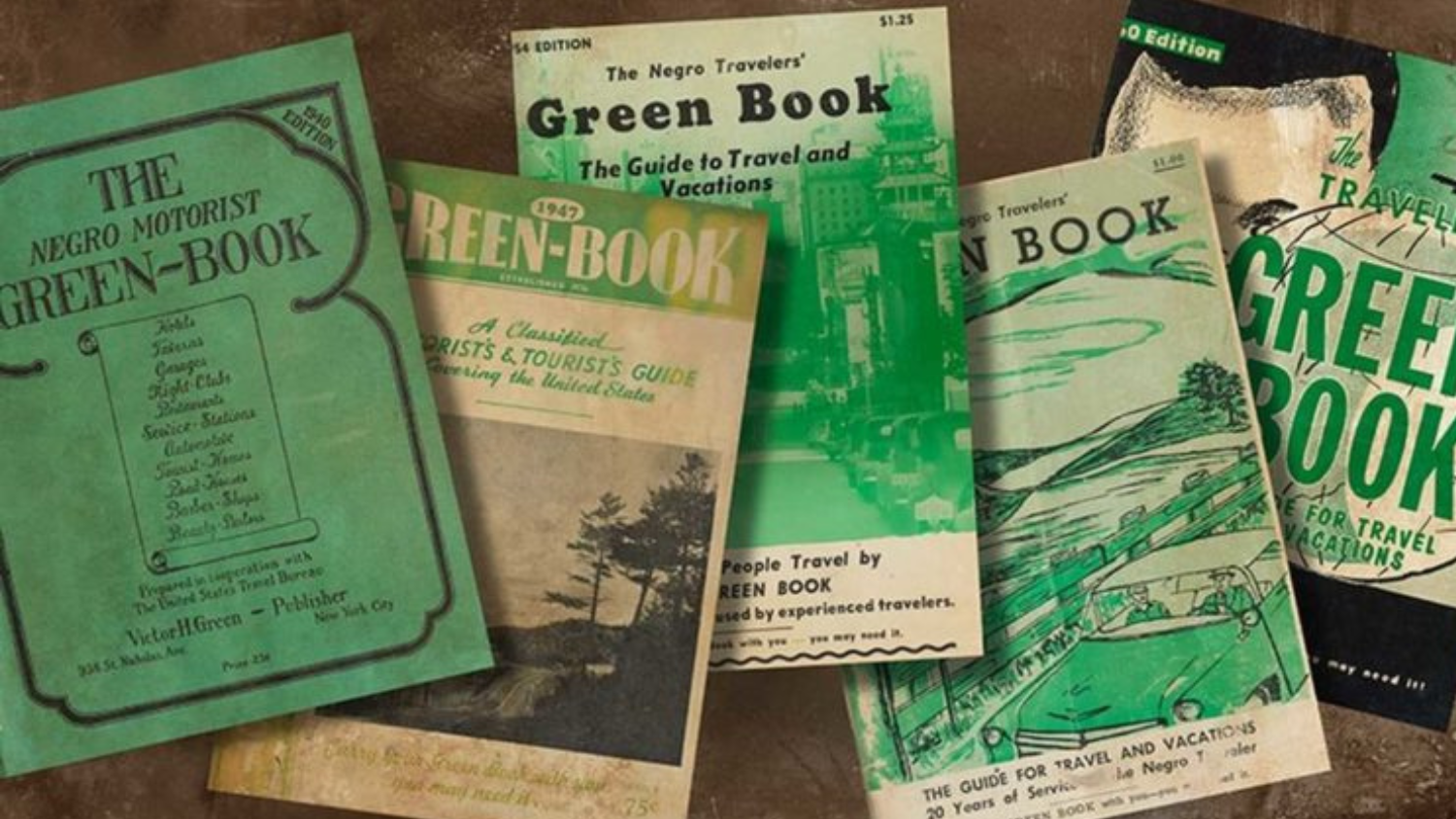

First published in 1936, The Negro Motorist Green Book was an essential resource for African American travelers, providing a directory of safe hotels, restaurants, and businesses in a time when racial discrimination made travel dangerous. The guide is now the subject of an exhibit at the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library in Washington, D.C.

Candacy Taylor, author of Overground Railroad: The Green Book and the Roots of Black Travel in America, collaborated with the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service and the D.C. public library system to bring the exhibit to life. It explores the history of the guide, named after its creators, Victor Hugo Green and his wife, Alma.

“We wanted to show people who were living their best lives in spite of what was happening around them,” said Taylor.

Navigating Segregation

During its publication years, from 1936 to 1967, The Green Book served as a crucial tool for Black travelers, helping them avoid places where they might face discrimination or danger. A centerpiece of the exhibit is a compass, symbolizing the guidance the book provided.

“It helps kind of orient you in this place, because, again, it wasn’t just the South that had racism. Jim Crow had no borders,” Taylor explained.

One of the greatest dangers faced by Black travelers was entering “sundown towns,” communities where nonwhite residents were banned after dark through law, intimidation, or violence.

Taylor emphasized the severity of the threat: “Some sundown towns had a bell that would ring at 6:00, telling the local laborers who were Black and the domestic workers that was their cue to get out of town. The consequences of you being in a sundown town were everything from harassment to death to lynchings.”

Unlike other travel hazards, sundown towns were not mapped, making it difficult for travelers to anticipate threats.

Documenting History

Taylor, a photographer and cultural documentarian, dedicated years to researching the locations listed in The Green Book, driving over 110,000 miles and capturing images of nearly 300 sites across 48 states.

“This guide was a license to leave. It was a way for people to find sanctuary and safety on the road,” she said.

Through her research, Taylor uncovered an unexpected aspect of The Green Book—the significant number of businesses owned by women, including hair salons and boarding houses.

“We’re talking about periods where women couldn’t even have bank accounts on their own, but we’re seeing them listed in this book, and that seems pretty powerful,” she noted.

Reflecting on these business owners, Taylor remarked: “I thought I knew a lot about Black history, and I came across all these women-owned businesses in The Green Book. And there were things called tourist tomes, which were kind of like—not quite boarding houses. Most of these tourist tomes were run by widowed women who had an extra bedroom and knew how to cook.

“And then, when I dug deeper and found the personalities of these women and interviewed some of the relatives of these women, they were fierce, and they were not just independent. I mean, they had real courage and skills in how to survive.”

A Personal Connection

Taylor’s research also led her to family history, particularly stories from her stepfather, Ron Burford.

Standing in front of his quote and chauffeur’s hat in the exhibit, Taylor shared, “Everybody had one, and you always kept it in the car.”

For many Black drivers, posing as a chauffeur for a white family was a survival tactic. Taylor recounted a harrowing experience Burford’s father had with a police officer:

“When the sheriff was walking towards the passenger door, his father turned around and said: ‘Shh. Don’t say anything.’

“And the sheriff says: ‘Where are you going? Whose car is this? And who are these people with you?’

“His father said: ‘I’m—this is my employer’s car.’ He looked at his wife and pretended he didn’t know her and said: ‘This is the maid, and that’s her son in the back, and I’m driving them home.’

“And the police officer said: ‘Well, where’s your hat?’ His father said, ‘I’m—it’s hanging in the back, Officer.’

“And Ron looked, and there was a chauffeur’s hat hanging there, and it had always been there.”

Taylor reflected on how sharing these memories deepened their relationship. “It was almost as though, when I did this project, he could trust me with his trauma. And it really gave me a different perspective and a lens to look at not only our history as Black people, but as his particular history as a dark-skinned Black man growing up in the South.”

Lessons from History

Although The Green Book is no longer needed today, Taylor stresses that the fight for justice is ongoing.

“The idea that just because time moves on that we get better as a country is not true,” she said. “When people say, oh, it’s 2025, why are we still dealing with this, or how could this be happening now, and when you learn about history, you will see that things don’t just march forward.”

However, Taylor finds inspiration in the work of Victor Green.

“It doesn’t take a lot to make change. He did this simple thing. He was a postal worker. He didn’t have up to an eighth-grade education. He had no resources. There were no computers. There was no Internet.

“And all of this happened with an idea. So, you don’t need to be rich, you don’t need a business degree, you don’t need all this stuff to make change.”

The exhibit, which runs through March 2, is also available online.

For PBS News Hour, I’m Gabrielle Hays in Washington.

Source: PBS