Jan 29, 2025 Story by: Editor

Charles Caldwell was never meant to have a voice. Mississippi’s white ruling class ensured it stayed that way.

In 1860, Caldwell was part of the state’s silenced majority—436,600 enslaved individuals compared to 354,000 white people, as recorded in the Census. After the Civil War, formerly enslaved individuals were granted full citizenship.

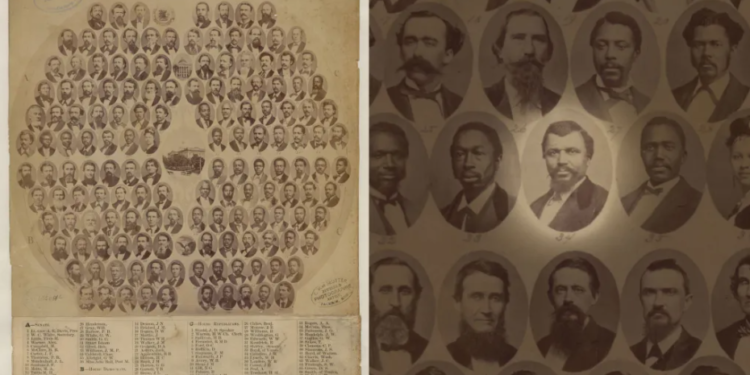

By 1868, Caldwell became one of 16 Black delegates at the state’s post-war constitutional convention, which granted voting rights to all men and laid the foundation for public education.

A white politician’s historical account of the Clinton Riot described Caldwell as “one of the most daring and desperate negroes of his day.” He was considered “the dominant factor in local Republican politics.”

In December 1875, Caldwell was tricked into a cellar for a Christmas celebration. He was ambushed—shot once from behind—then dragged into the street, where a white mob riddled his body with bullets. Rising from servitude to become a state senator, he was ultimately silenced once more.

His murder was a strategic act of white supremacist violence, part of the broader Mississippi Plan designed to maintain political dominance. In the post-war South, white supremacists used lynchings, massacres, and intimidation to suppress Black political power. The 1890 Mississippi constitution further entrenched racism, restricting Black voting rights.

While most racist sections of the 1890 constitution were dismantled during the Civil Rights Movement, one remains: felony disenfranchisement. This law permanently revokes voting rights for individuals convicted of crimes such as theft and bribery—offenses the 1890 drafters believed would disproportionately affect Black citizens.

A bill to restore voting rights for thousands convicted of nonviolent offenses passed the Mississippi House of Representatives in March 2024 but was blocked by the state Senate in April. Republicans control both chambers.

Section 241, which enforces disenfranchisement, has since been expanded to cover 102 crimes.

State Rep. James K. Vardaman, who later became governor, admitted the true intent behind the measure: “There is no use to equivocate or lie about the matter. … Mississippi’s constitutional convention of 1890 was held for no other purpose than to eliminate the n–ger from politics.”

Over the past three decades, approximately 55,000 Mississippians have lost their voting rights due to felony disenfranchisement, with nearly 60% being Black, according to state conviction records analyzed by The Marshall Project – Jackson.

Efforts to overturn Mississippi’s disenfranchisement law have reached the U.S. Supreme Court multiple times, only to be rejected. This Monday, the majority once again declined to take up the case. In her 2023 dissent, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson condemned the law’s racist intent, stating it contained “the most toxic of substances” that must be eradicated.

Beyond disenfranchisement, the 1890 delegates structured legal language around racism and conditions rooted in slavery. Poll taxes and literacy tests targeted Black citizens’ lack of wealth and education. Notably absent from Section 241 were violent crimes—murder, rape, and assault—often used as tools of white supremacist terror.

An 1896 Mississippi Supreme Court case acknowledged the racial motivation behind disenfranchisement. “Restrained by the federal constitution from discriminating against the negro race, the convention discriminated against its characteristics and the offenses to which its weaker members were prone,” the court wrote. Black people were described as “patient, docile people,” supposedly more prone to “furtive offenses than to the robust crimes of the whites.”

Despite the dismantling of many voting barriers by 20th-century civil rights laws, voter disenfranchisement persists.

“There’s never been a time period in Mississippi history where we have done what the federal government has wanted us to do without the federal government having to directly step in and make us do it,” said Hannah Williams, policy and research director for voting rights advocacy group Mississippi Votes. “Even now.”

Flonzie Brown Wright, the first Black woman elected to public office in a racially mixed town in Mississippi, reinforced this idea: “Movements change, but commitments don’t. Call it whatever you want to call it,” she told The Marshall Project – Jackson. “But the common denominator is: Let’s [not] give these minorities any power.”

Civil Rights Gains—and New Ways to Suppress Them

Mississippi is one of 13 states that imposes a lifetime voting ban even after the completion of a felony sentence. In most states, such bans apply only to violent crimes or government corruption. In Mississippi, a single felony conviction for writing a bad check or shoplifting permanently revokes voting rights.

Across the U.S., courts and legislatures have moved toward restoring voting rights to those with felony convictions. Since 1997, 26 states and the District of Columbia have expanded such rights, according to The Sentencing Project.

Mississippi last amended Section 241 in 1968, adding murder and rape as disenfranchising crimes after burglary was removed in 1950.

Despite once outnumbering white citizens, Black Mississippians have never held a majority in the state’s government. Robert Luckett, a civil rights historian and professor at Jackson State University, traced modern conservatism in Mississippi to the Mississippi Plan, which sought to eliminate Black political power.

“Conservatives today, especially in the South, didn’t just pop up out of nowhere,” Luckett said. In his view, “they are directly descended from segregationists, from white supremacy.”

Between 1875 and 1892, the number of Black voters drastically declined. While 67% had been registered in 1867, that number dropped to less than 6% by 1892, according to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights.

Beginning in the 20th century, economic and social hardships drove hundreds of thousands of Black Mississippians to leave during the Great Migration. By 1940, Black citizens were no longer the majority, and the racial hierarchy of slavery remained largely intact in many rural areas. Black sharecroppers worked land owned by white families.

With few exceptions, such as the all-Black town of Mound Bayou in Bolivar County, Black political influence in Mississippi remained minimal until the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.

Those who stayed faced brutal repression, including lynchings, beatings, intimidation, and imprisonment.

Rev. George W. Lee, a preacher in Belzoni, was assassinated in 1955 for trying to register Black voters. Civil rights leader Fannie Lou Hamer, who had been a sharecropper in Ruleville, didn’t learn she had the right to vote until she was 44. She was later arrested, sexually assaulted, and beaten so severely that she suffered permanent injuries. She testified about her experience at the 1964 Democratic National Convention.

Flonzie Brown Wright recalled that her father was fired from his job due to her activism. Before her groundbreaking election in 1968, over 1,000 civil rights protesters in Jackson were arrested and confined in livestock pens in 1965, marking one of the largest mass arrests of the movement.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 outlawed discriminatory barriers like literacy tests, enabling Black voter registration to rise to 60% by 1968. That same year, Mississippi elected its first Black state legislator since Reconstruction.

Despite her 1968 election, Brown Wright said systemic voter suppression persisted. She described efforts to deny her access to poll worker lists and disqualify Black candidates. She successfully sued to overturn these actions.

White leaders “never intended for Blacks to supersede or give the perception that we were in the process of gaining some semblance of equality. It was never intended to be,” Brown Wright, now 82, told The Marshall Project – Jackson.

Mass Incarceration as Modern Voter Suppression

Even as civil rights activism surged, a conservative movement pushed tough-on-crime policies that fueled mass incarceration—a modern means of suppressing Black political power. The rhetoric of criminality replaced overt racial discrimination, but the outcome remained the same: Black disenfranchisement.

Source: Mississippi Free Press