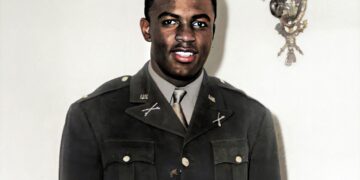

Willie Mays of the San Francisco Giants, 1969. (AP Photo) (1969 AP )

June 27, 2024 Story by: Editor

“Shut up!” insisted Willie Mays, the baseball legend who passed away last Tuesday at the age of 93. “Just shut up!”

In the summer of 1964, Mays gathered all the Black and Latino players on the San Francisco Giants in a Pittsburgh hotel room. Their manager, Alvin Dark, had been quoted making racist remarks about their intellectual and cultural shortcomings. Some of Mays’ teammates, including star player Orlando Cepeda, were considering boycotting games and demanding Dark’s dismissal.

Mays quelled the revolt. He explained that the Giants would likely fire Dark after the season anyway, and losing their manager mid-season would harm their pennant chase. He also warned that if Dark was fired, the media would relentlessly question them about quitting on their manager.

Mays reminded his teammates that when Dark appointed him team captain earlier that season, it had been seen as a deflection from another controversial interview about race. Critics argued that Mays’ captaincy was due to his race, not his merit, which added to his frustration.

“Don’t let the rednecks make a hero out of him,” Mays told his teammates.

This episode highlighted the burdens Mays carried. As part of the pioneering generation of Black players following Jackie Robinson into Major League Baseball, Mays faced racial controversies despite trying to avoid politics. He grew up during Jim Crow in Alabama and began his career in the Negro Leagues with the Birmingham Black Barons. Joining the New York Giants in 1951, Mays quickly impressed with his powerful and graceful play, earning Rookie of the Year and, in 1954, Most Valuable Player while leading the Giants to a World Series title.

Although Mays brought a cool demeanor to baseball, the press often portrayed him in a paternalistic light. Columnist Jimmy Cannon called him a “joyous boy,” and he was nicknamed the “Say Hey Kid.” This innocent image helped white fans embrace a Black athlete, but it couldn’t shield Mays from the prejudices of the 1950s. For instance, early in his career, Sports Illustrated faced backlash for a cover photo of Mays touching white actress Laraine Day. When the Giants moved to San Francisco in 1958, Mays struggled to buy a house in a white neighborhood despite the city’s liberal reputation.

In 1964, Dark told Newsday’s Stan Isaacs, “We have trouble because we have so many Negro and Spanish-speaking players on this team. They are just not able to perform up to the white ball player when it comes to mental alertness.” Although he considered Mays an exception, Dark believed most Negro and Spanish players lacked team pride compared to white players.

By quieting the unrest among his teammates, Mays was not capitulating to his white manager but acting as a pragmatic professional. He aimed to manage the situation to protect the players’ interests, including his own.

The controversy intensified during the Giants’ visit to New York City in early August for a series against the Mets. Rumors swirled about Dark’s potential firing, but most sportswriters, supportive of Dark, blamed Isaacs for misquoting him. Only Black writers and a few young, liberal white reporters defended Isaacs.

During a press conference at Shea Stadium, Dark touted his promotion of Mays to captain. After a closed-door meeting, Dark handed the lineup card to Mays, who, despite planning to rest due to a cold, penciled himself in to avoid accusations of undermining the manager. Remarkably, Mays hit two home runs, leading to headlines like “Mays Backs Dark with Two Homers” and “Mays: A Vote for Dark.”

When asked if he played to support Dark, Mays responded, “I don’t want to answer that.” Later, he clarified, “I never said anything like that.” Mays rejected any press-imposed role as the manager’s savior or an activist crusader, stating, “Who do you think I’m playing for?” He tapped his chest, saying, “Me.” He sought professional recognition, team victory, and financial reward, understanding that Black players faced different standards.

As Mays predicted, Dark was fired after the season, but Mays resented how the press exploited his words and actions. For the rest of 1964, he didn’t speak to Dark.

When Mays retired in 1973, his impressive stats included 660 home runs, 1909 RBIs, and a .301 lifetime batting average. Despite his late-career surliness, reflecting both his evolving personality and changing press sensibilities, Mays avoided publicly airing his feelings on racial injustice, unlike Jackie Robinson and other critics. Instead, he sought to bridge America’s racial divide by fostering goodwill.

When Mays died on June 18, tributes to his legendary career abounded. But it’s crucial to remember how the press used him to shape a story about race in America. Mays had his own story. Source: Yahoo news!