Oct 15, 2024 Story by: Editor

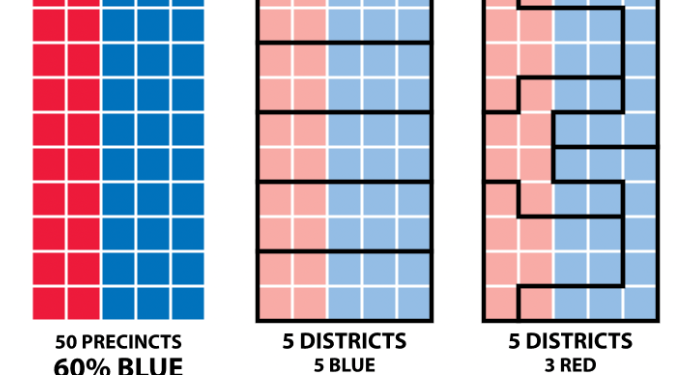

The principle of “one person, one vote” doesn’t fully apply in Georgia. As Georgia residents witness the disparity between the ideal of equal voting rights and the actual disillusionment with the electoral process. Georgia’s state legislature has turned redistricting into a partisan tool, manipulating congressional boundaries to influence election outcomes — a practice known as gerrymandering. Ideally, redistricting should serve to allocate populations fairly across geographic districts, not become a political maneuver.

Although the state is almost evenly split between Republicans and Democrats, racial gerrymandering has skewed representation. Currently, only one out of 14 congressional districts is competitive, with the remaining 13 largely dominated by partisan interests. Congressional boundaries are drawn to secure a 9-5 Republican advantage, making it difficult for Georgians to voice their preferences on elected officials. Despite federal election results that lean Democratic, such as President Biden’s 2020 victory — the first Democratic presidential win in Georgia since 1992 — and the election of two Democratic senators, gerrymandering has preserved Republican supermajorities in statewide representation. In response to growing diversity in Atlanta suburbs, Republicans have increasingly relied on gerrymandering to maintain power.

While some states have taken steps against racial gerrymandering, it remains common and is often upheld by conservative courts. Georgia’s shifting federal voting patterns suggest that congressional representation should reflect these changes. Instead, gerrymandering disrupts this alignment by securing GOP dominance in both the state legislature and the congressional delegation, effectively preventing voters from choosing their representatives.

The consequences of gerrymandering go beyond party composition, challenging essential democratic values like freedom and choice. When district maps are manipulated to protect incumbents and avoid competition, elections become “a mere ritual to verify the predetermined result,” leading to political disengagement and public apathy.

Moreover, gerrymandering reinforces racial inequalities, a strategy that conservative courts continue to support. In many southern states, only one district typically has a majority of minority voters, even though minority populations are significant statewide. Public opposition to this practice increased after the 2019 Supreme Court decision that limited federal courts from intervening in cases of partisan gerrymandering. The ruling established stricter standards for what violates the “one person, one vote” principle, leaving federal courts to address only issues of population imbalances and racial discrimination.

Although federal courts now face limits in redistricting matters, the Supreme Court continues to issue varied rulings on gerrymandering cases. In 2023, anti-gerrymandering activists saw a victory when the Court ruled that Alabama must create a second majority-Black district under the Voting Rights Act. In that case, the challenged map had just one majority-Black district, despite Black voters making up 27% of Alabama’s voting-age population.

However, the Court doesn’t always side with civil rights advocates. In 2024, it dismissed an NAACP argument against South Carolina’s congressional map, with Justice Samuel Alito stating that partisan, not racial, factors likely influenced the district lines. This decision moved 30,000 African-American residents out of Charleston’s district, demonstrating how conservative courts can protect partisan redistricting practices. Despite some rulings, like Alabama’s, limiting racial gerrymandering, the tactic remains an entrenched issue in U.S. politics.

Georgia’s voters who experience vote dilution have also found little relief in the court system. While new majority-Black districts were created in the state Senate and House, Republicans made adjustments in other areas to offset these changes, strengthening conservative prospects in places like Atlanta’s 7th Congressional District. The Voting Rights Act protects minority voters, but doesn’t prevent altering Democratic-leaning districts with white majorities or areas without a majority ethnic group. While Georgia’s adjustments are less overt than South Carolina’s, the state legislature still carefully tailors district lines to protect political power.

The unpredictability of the U.S. judiciary in cases involving voting rights and disenfranchisement is underscored by recent decisions. A more consistent remedy has emerged through independent commissions. For example, Michigan’s GOP-led map previously diluted African-American votes in Detroit, merging suburban Oakland and Macomb with parts of the city to increase Republican seats. The Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission (MICRC), however, addressed racial gerrymandering by creating fairer districts, including the 6th, 13th, and 14th, now centered in suburban Oakland and Macomb counties to improve urban representation. The MICRC, rather than the legislature, oversaw redistricting, resulting in a more proportional map.

What could help in Georgia? A similar ballot initiative to Michigan’s redistricting reform could shift the dynamic here and across the South. Bipartisan support for such initiatives, which use commissioners and legal experts to evaluate fairness in district lines, is growing. Ohio, for instance, proposed a citizen commission with five Democrats, five Republicans, and five independents to oversee redistricting. Georgia and other states might benefit from a similar structure, especially when legislatures currently control map-drawing.

Although recent rulings, such as South Carolina’s, are worrisome, independent commissions continue to foster hope for fair representation. While racial gerrymandering has faced pushback in states like Alabama, it remains a fundamental issue that hinders democratic accountability. Georgia stands at a pivotal point, as ongoing legal efforts seek outcomes like the Supreme Court’s mandate for Alabama to redraw biased districts. Source: Harvard Political Review