Oct 13, 2024 Story by: Editor

Leading academics are sounding the alarm that Black scholarship in the UK is at risk of being eliminated due to redundancies and course closures.

As universities in England grapple with a financial crisis, they have implemented various cost-cutting measures. However, many prominent scholars and students are raising concerns that these cuts disproportionately affect lecturers and courses vital to addressing racial disparities in higher education.

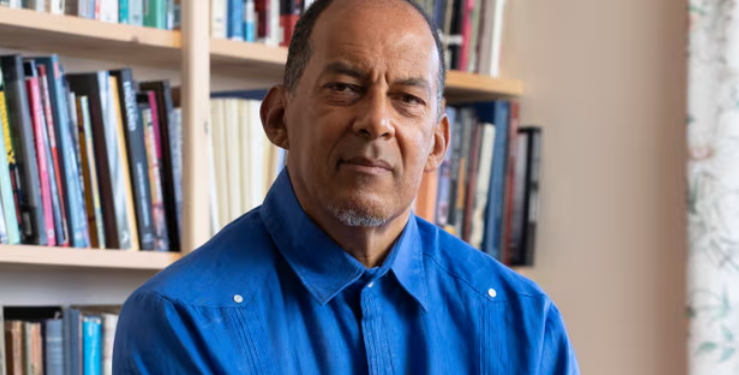

The University of Chichester has made Professor Hakim Adi redundant and discontinued his MRes program focusing on the history of Africa and the African diaspora. At the University of Winchester, well-known theologian Professor Robert Beckford, who researched climate and social justice, has also lost his position. Meanwhile, Birmingham City University (BCU) has shut down its undergraduate course in Black studies.

In contrast, Goldsmiths, University of London, has reversed its decision to cut the Black British literature MA after receiving significant backlash, committing to run the course for an additional two years. However, it recently laid off Professor Deirdre Osborne, the course’s founder and convener. Kadija George Sesay, one of the writers who signed an open letter criticizing this decision, told the Guardian that she returned her honorary fellowship to Goldsmiths in protest.

Over the past decade, there have been significant advancements in creating dedicated lectureships and developing broader curricula focused on Black history, culture, politics, and philosophy within higher education. These efforts, coupled with active mentoring and recruitment of academics of color, have led to an increase in the number of Black professors in the UK.

Despite this progress, universities argue they are facing a severe financial crisis, stating that these courses are expensive to operate and do not attract as many students as similar programs in the US, where the discipline of Black history and arts is more established.

Advocates emphasize that these courses and the specialized knowledge of their instructors should be protected, as they require time and support to make a meaningful impact. Currently, fewer than 1% of professors in the UK are Black.

Beckford remarked, “The reality is I’ve never been in a job since 1993 which has been secure. I’ve always had the threat of redundancy because there was always a lack of funding for posts that were connected to race. I’ve never had that kind of luxury of knowing that I was in a place that was going to invest in me and give me lots of time to develop my craft.”

He added, “You get a freeze on the development and mentoring by jettisoning people like me. My work has always been fundamentally about empowering Black students, empowering Black colleagues.”

While the University of Winchester declined to comment on specific cases, a spokesperson stated that “all the redundancies upon which we have consulted reflect the challenging financial circumstances facing the university sector.”

Professor Kehinde Andrews, who heads the Black studies department at Birmingham City University, expressed disappointment but not surprise at the course’s termination. “There’s no appreciation for the importance of Black intellectual thought, so they get rid of it really easily. I think that’s what you’re seeing everywhere. You can’t even call it erasure because there’s so little Black production in Britain. It’ll be completely wiped out; there’ll be nothing left.”

BCU chose not to comment further.

Prof. Adi believes these cuts will severely impact the number of Black history professors in the UK. The master’s program he oversaw produced seven students who went on to pursue PhDs, six of them at Chichester. “We were particularly trying to redress the imbalance in higher education: the fact that there were so few students of African and Caribbean heritage studying history at postgraduate level in this country,” he said.

The students in Adi’s course have initiated a legal challenge against the university, claiming discrimination and breach of contract after the program was terminated while they were still enrolled.

A spokesperson for the University of Chichester stated that while it had made the “difficult decision” to suspend several courses, current master’s students “were encouraged to complete their studies with us and were offered appropriate tuition.”

Osborne expressed her heartbreak upon learning of her redundancy earlier this month. “What kind of message does removing opportunities for access to that knowledge send to students and future generations of Black creatives?”

Dr. Stephen Graham, Goldsmiths’ executive dean of faculty, emphasized that the MA program was essential for fostering Black scholarship and enhancing diversity within academia. “These were the reasons both behind the creation of the MA program and our persistence in supporting it in the face of low recruitment numbers,” he noted, acknowledging the concerns regarding the financial challenges facing universities and their effects on Black scholarship.

A student enrolled in the Black British literature program, who wished to remain anonymous, shared their disappointment: “I joined the course because of the professor, who is a leading academic in the space. I absolutely trusted her experience, vision, and commitment – that has now been taken away. New students have arrived from overseas who spoke to the professor, made a significant financial and personal commitment, and that professor is simply not there.”

Graham responded, “The course is being taught by two leading Black scholars, and over the next two years, we will work to develop a more multidisciplinary program that will help in attracting more students.” Source: The Guardian