Nov 20, 2024 Story by: Editor

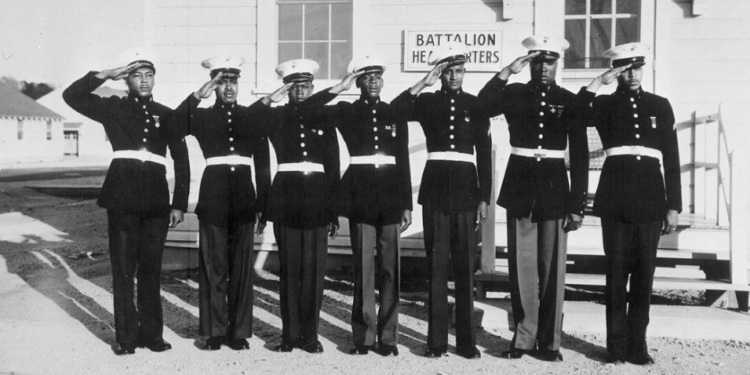

A striking, large-scale photo captures U.S. Marines saluting in perfect formation, their crisp dress uniforms instantly recognizable. However, when this photo was taken in the 1940s, it likely raised eyebrows as it shows one of the first images of Black Marines. This was a time when the Marine Corps had only just begun to form divisions for Black men during World War II.

The photo is part of Fighting for the Right to Fight: African American Experiences in World War II, a special exhibition that opens on Veterans Day (Nov. 11) at The National WWII Museum in New Orleans. The exhibit highlights the contributions of over 1.2 million African Americans who served in World War II, including thousands of drivers and logistical support workers, the 6,500-member all-Black Women’s Army Corps Unit, and the famous Tuskegee Airmen. Black Americans volunteered in unprecedented numbers to serve in all branches of the military, while at home, over 1 million worked in the U.S. industrial sector, supporting the war effort globally, said Pete Crean, the museum’s vice president of education and access and an Army veteran.

“A lot of the history of African Americans in World War II is hidden, unknown or missing,” said Crean. With the exhibit’s collection of historic photos, films, artifacts, and wartime Black press clippings, it shines a light on their often-overlooked story. Among the items on display are military gear, medical instruments, and even a worn wooden ballot box that symbolizes the challenges Black Americans faced regarding their voting rights during this period.

One notable display includes a U.S. Navy jumper and hymnal that belonged to Freddie Meeks, a Black sailor court-martialed and jailed for refusing to return to his hazardous job after a deadly explosion on ammunition ships. He and other protesters were later exonerated.

The exhibit also includes interactive features such as video interviews with elderly veterans. These veterans, featured in “We Were There” exhibits, answer visitor questions using AI technology, offering a lifelike interaction that was months in the making.

First launched in 2015 and after a successful tour across 12 cities, this expanded version of Fighting for the Right to Fight now occupies a spacious gallery at The National WWII Museum. It begins by exploring the long history of African Americans in the U.S. military, stretching back to the Revolutionary War. A central theme of the exhibit is the “Double Victory” against both global fascism and entrenched racism, a term coined by a Black American newspaper during the war. Another section focuses on the post-war impact of Black military service, particularly as veterans returned to Jim Crow-era states and became active in the Civil Rights movement.

“Many of the Black members of the military took their uniforms off and became leaders of the Civil Rights movement,” Crean explained.

The exhibit also addresses military integration, highlighting President Harry Truman’s July 26, 1948, executive order to desegregate the armed forces. Guest curator Krewasky A. Salter, PhD, a military historian and retired U.S. Army colonel, played a key role in the exhibit’s development. He previously served as president of the Pritzker Military Museum & Library and as a guest curator at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.

“It has been a privilege to work with The National WWII Museum to significantly expand and give this important exhibition new life,” said Salter. “The contributions and legacies of African American service during World War II cannot be overstated. Fighting for the Right to Fight recognizes the paths forged by Black service members, civilians, and veterans, and serves as a reminder of the continued struggle for justice and equality today.”

Visitors to the exhibit will also confront the fact that during World War II, Black military personnel were not eligible for the Congressional Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest award for valor. It wasn’t until the Clinton administration that a review of Black military records led to the recognition of seven African American service members, who were awarded the Medal of Honor in 1997—most posthumously. One such medal, belonging to Army Staff Sgt. Edward Carter, is on display as a tribute to the valor of Black service members who fought despite not being fully integrated into American society.

“A lot of African American families will mention to you that grandfather or father was involved,” Graff said. “The work and the struggles of their relatives are finally being moved out to the light. We talk a lot about Midway, the Battle of the Bulge, we talk about Gen. George Patton a lot. These other people who were also very important are being acknowledged, but it took decades, and we are very proud to have been a part of it.”

The exhibit will be on display in the museum’s John Alario Jr. Special Exhibition Hall until July 27. Source: NOLA