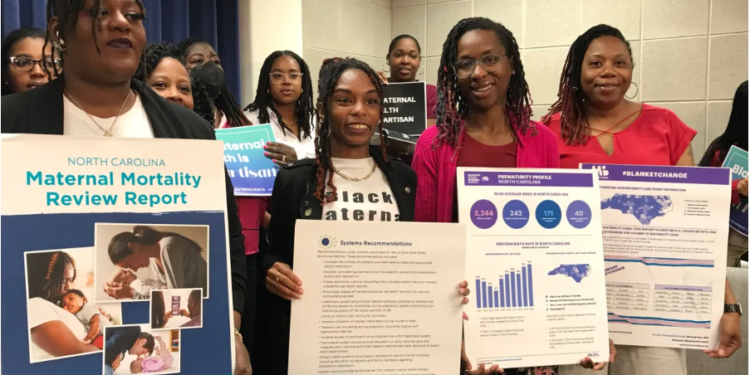

A group of advocates for better maternal health care hold up printouts with statistics about prematurity, maternal mortality, and recommendations to improve both in the health care system. Credit: Rose Hoban

June 27, 2024 Story by: Editor

When Charity Watkins discovered she was pregnant in 2016, she meticulously followed all the recommended guidelines to ensure a healthy pregnancy. Watkins, then a doctoral student, was diligent about prenatal care, attending birthing classes with her husband, reading pregnancy books, and maintaining a healthy diet and exercise routine.

“I initiated prenatal care when my husband and I enrolled in birthing classes, I read books on what to expect and took extra care to ensure I ate well and exercised throughout my pregnancy,” said Watkins, who is Black.

Now a maternal health researcher at Duke University and an assistant professor at North Carolina Central University, Watkins actively participated in obstetrical visits, asking questions, sharing her family’s medical history, and participating in online communities for expecting parents.

Despite her efforts, Watkins experienced a life-threatening complication a day after giving birth, ending up in the intensive care unit with peripartum cardiomyopathy, a type of pregnancy-related heart failure.

“It was only through X-rays that I finally understood what was happening,” Watkins said. “But why did it take so long? Why weren’t my symptoms taken seriously? Why couldn’t my doctoral education protect me?” she asked. “My daughter almost lost her mom, and my husband almost lost his wife.”

The U.S. maternal mortality rate is among the highest in the developed world, and it is notably worse for Black women, who are three times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than white women in the United States.

In North Carolina, the maternal mortality rate more than doubled from 2019 to 2021, increasing faster than the national rate, according to a report from last year. Black women represented 43% of pregnancy-related deaths in the state from 2020 to 2022, despite making up only 22% of North Carolina’s population.

Democratic state lawmakers are advocating for Senate Bill 838, aimed at improving maternal health and addressing disparities affecting Black mothers. At a news conference where Watkins shared her story, legislators and advocates pushed for the bill’s passage. The bill, also known as the “MOMnibus,” would establish an implicit bias training program for healthcare providers in perinatal care and fund grant programs for perinatal education. It would also outline the rights of perinatal care patients and allocate $5 million for these initiatives. Additionally, the bill would require the state Department of Health and Human Resources to collect data on the causes and rates of maternal mortality to enhance future implicit bias training.

Senator Natalie Murdock of Durham, a primary sponsor of the bill, urged Republican lawmakers currently crafting the budget to allocate funding for the bill. “We know our colleagues have bragged about a billion-dollar surplus so I think they can find $5 million,” she said.

“Black moms and Black babies deserve better,” Murdock emphasized. “We must invest state dollars to improve these outcomes, and we must pass legislation that directly addresses these issues and racial disparities and inequalities in maternal health.”

Black mothers are not the only group experiencing disproportionate health outcomes in North Carolina. Although the state’s infant mortality rate slightly improved from 2021 to 2022, Black babies in North Carolina remain more than twice as likely to die before their first birthdays compared to white babies, according to a CDC report.

“We know that there are those who somehow believe that we take pain differently than we don’t need medication,” said Rep. Zack Hawkins (D-Durham). “But what it does boil down to is that in the medical space, we need to make sure that every doctor that wants to go into the space has the training to deal with all population.”

According to data from Maternal Mortality Review Committees, over 80% of maternal deaths are preventable. MMRCs are multidisciplinary teams that review deaths during or within one year of the end of pregnancy at the state or local level.

“We are experiencing a crisis here,” Watkins stressed. “Improving the maternal health of Black women improves the health of all. We cannot afford to wait for action; legislation like the “Momnibus Act” is needed now; our lives depend on it.”

Unfortunately, the House budget proposal released by Republican lawmakers late Monday does not include the requested funds. Source: NC NEWS LINE